ALLOW ME TO REVIEW THIS THROUGH PICTURES…

***

Nigerian Modernism is written in huge orange letters on a yellow wall at the exhibition’s entrance in the Tate Modern. It showcases the work produced by artists in the decades before and after Nigerian independence from British colonial rule. According to Curator of International Art Osei Bonsu, Nigerian Modernism shows off over 300 works from over 50 artists, and endeavours to inspire intergenerational conversations around Nigerian art, culture and music to name a few.

I felt at home moving through the various rooms in the exhibition, following a choreographed layout that the curators pulled of effortlessly. I looked into the past when witnessing the artists’ demonstrations of everyday Nigerian life, to battle, politics and mythology shown in their artwork. Below I explore the art that captivated me the most.

Justus D. Akeredolu – Thorn Carvings – 1930s

These were such a pleasure to look at. They depict moments and customs from everyday Nigerian life around the 1930s. Akeredolu first began creating these sculptures when carving the handles on name stamps (stamps you could use to print your name on a letter). He would use thorns of the silk cotton tree to do this. Eventually, he began using these thorns to make his Thorn Carvings. Akeredolu then taught this technique to his apprentices.

I like how fun and whimsical the carvings feel. The backbend one is my favourite. There’s a fun yet delicate nature to the pieces. Because of their size, they come across as collectibles.

Akinola Lasekan – Ogendengbe of Ilesha in Kiriji War:

The Celebrated Battle of Ekiti-Parapo Independence, c.1958–1959

In this painting, Akinola Lasekan depicts Yoruba chief and warrior Ogendengbe of Ilesha on horseback during Nigeria’s Kiriji War, also known as the Ekiti–Parapo War. He served as commander-in chief. The war, which took place between July 1877 and March 1893, mainly occurred to halt the attempted expansion of Ibadan city state.

There’s a majestic nature to Ogendengbe’s posture on horseback as he and fellow warriors look out to the landscape. Not often do I see depictions of 19th century Yoruba wars on canvas (believe it or not). This painting captivated me.

Akinola Lasekan – Yoruba Acrobatic Dance, 1963

When art captures a specific moment of motion it causes us, the viewers, to be captured as well. This was so beautifully executed by Lasekan here. The colours are to be expected in any artwork from such a vibrant people, so the juxtaposition between this and the expressive stillness is really gripping. To a degree you can hear the pin-drop silence of the painting as the dancer levitates. It made me want to press play to see him land and experience the motion of the crowd when he does. It’s just a cool piece of art!

Akinola Lasekan – MacPherson Constitution political cartoon

This drawing, also by Lasekan, was part of a collection of political cartoons on display. I was most drawn to this one it because of the stone the imperialist was carrying, with “Macpherson Constitution” written across it. I did a bit of research. Established in 1951, the constitution divided Nigeria into three regions – Northern, Western and Eastern. It was Britain’s attempt to give the citizens more political say by virtue of legislature and councils in each region.

By producing these cartoons, Lasekan engaged in anti-colonial art activism. This is because their narratives spoke against the Macpherson Constitution and much more. The constitution was not the clear independence that people desired. Rather it was Britain’s way of upholding its imperialist presence in Nigeria.

This is something Tate’s exhibition does well – straddling the historical and the political elements of Nigerian Modernism, through the differing mediums of work explored by artists like Lasekan.

Ben Enwonwu – The Dancer (Agbogho Mmuo – Maiden Spirit Mask), 1962

This is a painting of a masquerade, most typically worn by men. The loose translation of Agbogho Mmuo is “Maiden spirit”. This masquerade honoured ancestors and unmarried young girls. Enwonwu drew inspiration for this painting and similar others from a book called Africa Dances by a British anthropologist named Geoffrey Gorer. The book critiques Britain’s colonial rule of West Africa.

Growing up, I only ever heard scary stories about masquerades, and I would probably still be scared if I saw one the next time I’m in Nigeria. However I can’t deny how beautiful they can be, as depicted by this very painting. The craftsmanship of masquerades alone is admirable. As a Christian it opens up questions for me, especially being raised to have distaste for anything to do with Nigerian/African spirituality. Yet, it feels like a waste of heritage to maintain an aversion to the history of my culture – being in the UK removes me enough. The masquerade’s posture and motion captured by the brushstrokes are what I enjoy about this piece. You can get a closeup of the painting here.

Ben Enwonwu – Seven Wooden Sculptures – 1960-61

You can’t miss these wooden sculptures in the middle of the second room in the exhibition. It was a bit difficult to find out exactly what they were, but a bit of research taught me something. These seven sculptures were made by Ben Enwonwu for the Daily Mirror’s new headquarters that were opening in Holborn, 1961. Enwonwu had been commissioned by the paper following his growing popularity after producing a statue of Queen Elizabeth in 1957 and another well-known sculpture called Anyanwu in 1956.

I was so drawn to the expressions endowed upon the sculptures as they represented reactions to the Daily Mirror’s reports. As for the transformation of the newspapers into winged shapes, Enwonwu, said, “I have tried to represent the wings of the Daily Mirror, flying news all over the world… The group forms a sort of chorus. It is almost a religious group. All art, I believe, has a religious feeling – a belief in humanity.”

In 2013 the sculptures were sold for £360,000 at Bonhams after they were discovered in a garage at Bethnal Green Academy in East London. It’s unclear how/why they were removed from the Daily Mirror’s HQ.

Ben Enwonwu – Untitled, 1960

Something about this painting reminded me of a popular painting by Annie Lee, called Blue Monday. She painted it in Chicago, 1985. The posture and blue hue of the top worn by the woman in Enwonwu’s painting is reminiscent of Lee’s piece . There’s not much information about Untitled in the exhibition and I couldn’t find much about it online. But there’s a pensive nature to the painting – a woman alone and deep in thought. I think anyone can see themself in this picture.

It was a refreshing piece to see among the other artworks with more outstanding narratives and acts of socio-political resistance. There of course remained moments pre- and post-independence where Nigerians paid great attention to their inner worlds just like anyone else. The world moves around us just as much as it moves within us. That’s what this piece represented to me in the space.

Ben Enwonwu – Fulani Girl, late 1940s

One of my aunties always calls me Fulani girl. According to her, I look like I am from that region of Nigeria. This physiognomic comment always felt like a nod to the interconnectedness of Nigerian tribes, despite the distinctive nature of them all. So the name of this beautiful sculpture, carved from a piece of ebony wood, drew me in when I first saw it.

Fulani girl was purchased by the Government Art Collection (GAC) in 1951. The collection displays works of art in British government buildings in the UK and around the world. Around the time it was sold, Enwonwu was passionate about his artwork being displayed in government spaces as he believed they would promote Nigerian art and culture. That’s a different tune to what we’re used to hearing around the collection of art from colonised countries. The bust itself looks so smooth and peaceful, and I’m led to wonder if it’s a depiction of a certain girl, or Fulani girls as one. According to GAC, the arch and general design of the sculpture is a fusion of Nigerian aesthetics and European art with aim to reimagine Nigeria itself.

Ladi Kwali – Ceramic artist

This entire room, painted the most beautiful shade of orange, was dedicated to potter and ceramicist, Ladi Kwali. Initially taught by her aunt, she specialised in traditional Gbagyi/Gwari pottery – the region she was from in central Nigeria. The room featured dishes, water pots, plates and cups/drinking vessels that Kwali made over her lifetime, charaterised by scoring, sgraffito and animal drawings against the dark glossy glazes.

This room emphasised Kwali as an artist, above a producer of domestic utility items. Her practise required immense technique and talent that deserves to be celebrated – and a room being dedicated to this celebrates that. Kwali went on to be the first woman to join the Pottery Training Centre in Abuja, 1954, and the only woman to be featured on Nigerian currency (the 20 Naira note).

You can see that I had the time of my life in this room. I feel excited when I see a Black person doing pottery on my fyp, talk less of a whole room dedicated to this greatness. I had never heard of Ladi Kwali before this exhibition, and now, or course, I will never forget!

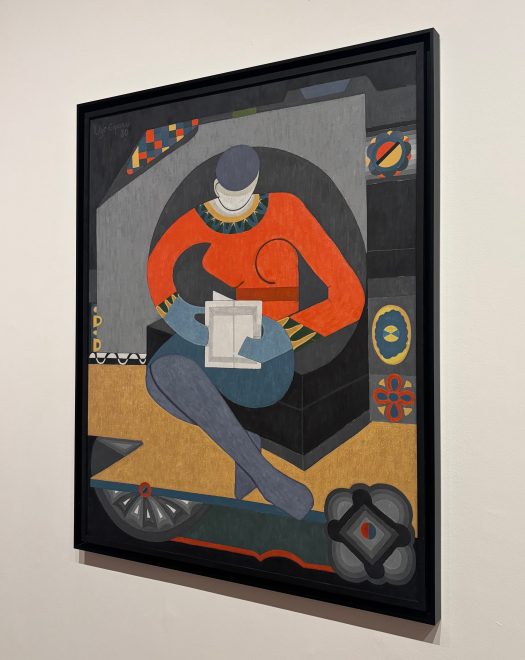

Uzo Egonu – Poetess – 1980

This feels like a perfect artwork to end on. It was created closer to the end of the 20th century and Egonu lived in Britain while Nigeria was experiencing extreme corruption following the oil-induced economic boom of the 1970s. Parallel to this social change was Egonu’s loss of sight due to the harsh materials he worked with for his paintings – there was deterioration both within and around him. Tate called this room, “Uzo Egonu: Painting in darkness”. Poetess, the striking painting above, is part of a collection of artworks that Egonu named Stateless People. It was first exhibited in 1986 London and he stated, ‘My stateless people are far from being political or religious refugees. They are people who are symbolically stateless.‘

Poetess depicts a poet with presumably, her poetry. The others in the collection depict a musician, an artist and a writer. In all the paintings they are bent over their work. These people are symbolically ‘stateless’ because they are frustrated visionaries from a Nigeria that in Egonu’s eyes was yet to be commendable post-independence. It’s a critical perspective and Egonu was known for having such. He refused categorisation and was a radically independent artist.

***

Final thoughts

Painting in darkness was a balanced note to end the exhibition on, as often reflections on a nation post-independence can be quite sensational and lack nuance. It’s never a pleasant process to unpack the (lack of) progress a nation has made following centuries of trauma, however necessary to try. But even so, the beauty of art and culture produced by it are to remain celebrated.

In case you can’t tell, this is a very positive review of Nigerian Modernism at Tate Modern. I felt pictures are the best way for me to communicate why I enjoyed it, rather than an overall written piece with few visual references. I haven’t even scratched the surface of the vast number of artworks on display and the depth of information each room invites you to engage in from the entrance and throughout. There are rooms with films, highlife music, pamphlets, magazines, poetry, photography and more. So go and have a look! Hopefully this is enough of a taste of what you can expect in this well-curated exhibition.

A really lovely piece. “The world moves around us just as much as it moves within us” wow!!

LikeLike

happy you like it, i truly recommend!

LikeLike